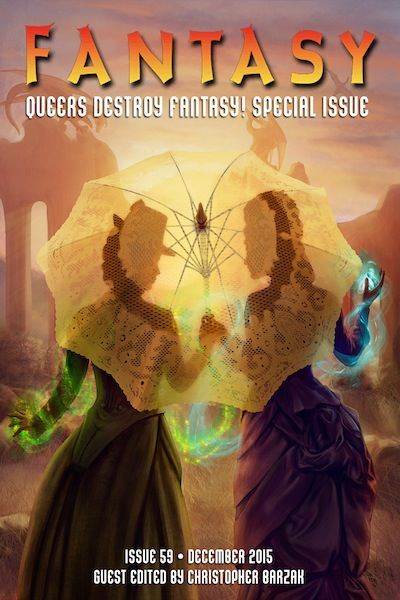

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. For December, I talked about The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2015 edited by John Joseph Adams and Joe Hill—and this time, I’d like to look at another installment in the “Destroy…” series of special issue magazines, Queers Destroy Fantasy. Christopher Barzak edits the original short fiction, while Liz Gorinsky takes care of the reprint fiction; Matt Cheney is the editor for the nonfiction.

This is a more compact issue than a few of its predecessors, but the mix of styles and tones conveying the “fantasy” motif worked well together to create a fairly balanced reading experience. There are four original pieces and four reprints, plus a novel excerpt for Charlie Jane Anders’s upcoming All the Birds in the Sky. Since I’ll be discussed that book as a whole soon enough, I’d like to focus on just the short fiction offerings this time around (and though the nonfiction isn’t under the remit of this column, it’s definitely worth checking out too).

The first piece of original fiction, “The Lily and the Horn” by Catherynne M. Valente (illustrated by Goñi Montes), has the feel of a lushly illustrated vignette—a captured moment full of nostalgia and poetry, though little traditional movement. The action is a held-breath build: waiting for the protagonist’s lover, a woman whom she went to a sort of poisoner’s finishing school with, to arrive to “battle” her (though the two will not speak or touch or interact, and it’s all via proxy). That moment of breathless waiting, kept apart by politics and the nature of marriages for those politics, is the centerpiece of the story, and it works. The imagery is also quite stunning, so the poetics of the piece are well executed.

The first piece of original fiction, “The Lily and the Horn” by Catherynne M. Valente (illustrated by Goñi Montes), has the feel of a lushly illustrated vignette—a captured moment full of nostalgia and poetry, though little traditional movement. The action is a held-breath build: waiting for the protagonist’s lover, a woman whom she went to a sort of poisoner’s finishing school with, to arrive to “battle” her (though the two will not speak or touch or interact, and it’s all via proxy). That moment of breathless waiting, kept apart by politics and the nature of marriages for those politics, is the centerpiece of the story, and it works. The imagery is also quite stunning, so the poetics of the piece are well executed.

Then there’s “Kaiju maximus®: ‘So Various, So Beautiful, So New’” by Kai Ashante Wilson (illustrated by Odera Igbokwe)—a story I found intriguing in part for the fact that it’s about a couple whom one might consider, in some manner, straight. Except there’s an intense reversal of gendered expectations between the hero and the hero’s beloved, and that’s what gives the story its punch. The world presented in it is also intriguing: the kaiju, the video-game references and the scientific asides, all give us an odd sense of unreality against the backdrop of nomadic familial struggle, a relationship that is fraught and dangerous, and the emotional core of sacrifice that the protagonist is made for. I liked it, though I did feel that I’d have liked more out of the story—it’s doing a lot of interesting things, but still seemed a bit unbalanced at the end in terms of development of its themes and threads.

Our next piece has a more horror-story vibe: “The Lady’s Maid” Carlea Holl-Jensen. It’s got some Countess Bathory-esque weirdness, and the erotic relationship between the Lady and her maid is even more bizarre and discomfiting. It also treads a line of sadism and nonconsensual interaction that gives the horror a further edge of squick, though there seem to be hints that the Lady is perfectly aware of the things that happen if she takes her head off and leaves the maid reign over her body. All the same, it’s got one strong central visual and a powerful twist of body-horror; as a story, though, it didn’t necessarily hold my attention and interest throughout.

“The Dutchess and the Ghost” by Richard Bowes (illustrated by Elizabeth Leggett) is the only one of the four original stories that has a traditional sense of plot arc and a solid conclusion that, nonetheless, leaves the reader pleasantly thoughtful. Having thought it over for a bit, I suspect this is actually my favorite piece of the bunch: it deals with being queer and running away to New York in the early sixties, the cost of freedom, and the cost of being one’s own self. There’s an unvarnished handsomeness to the narrator’s descriptions that lends the piece an honest, realist air, even though it’s about ghosts and time and death. It blends together its fantastical elements with its mundanity very well.

There are also the four reprints, curated by Liz Gorinsky. “The Padishah Begum’s Reflections” by Shweta Narayan (illustrated by Sam Schecter) was originally published in Steam-Powered: Lesbian Steampunk Stories edited by JoSelle Vanderhooft (2011); unsurprisingly, it is a lesbian steampunk story. More interesting is the approach to the trope. Narayan gives us a perspective on the Napoleonic conflict through the lens of mechanical Empress Jahanara—who doesn’t really have a lot of patience for the petty squabbles of Europeans, but is more concerned with securing her kingdom and the love of the French artisan and craftswoman whom she’s had a long epistolary communication with. I do appreciate the sense of building a woman’s world the way that Jahanara does, as well. This is a feel-good story, rather sweet, though the steampunk thing doesn’t do it for me much.

“Down the Path of the Sun” by Nicola Griffith was originally published in Interzone (1990). After the plague, our protagonist is living with her mother and younger sister; her lover Fin also lives with her female relatives. Things have been peaceful until the sudden and brutal assault and murder of the protagonist’s little sister by a roving gang. The description of loss and trauma is intense, here. Griffith has a handle on the things that dig under a reader’s skin like fish-hooks. It’s short but evocative.

Originally published in One Story (2006), “Ledge” by Austin Bunn (illustrated by Vlada Monakhova) takes the idea of the edge of the world and makes it real: the sailors in this piece discover the path to purgatory over the ledge, and bring back lost souls of the dead. The idea is interesting, but I found myself a little frustrated that it’s another piece where historical homophobia is The Thing. While the ending here is the strong point—it manages to encompass the horror of defeating death alongside the joy of it—I thought the piece itself ran rather slow.

The short fiction ends with “The Sea Troll’s Daughter” by Caitlín Kiernan, from Swords & Dark Magic: The New Sword and Sorcery (2010), and it was the best of the bunch in the reprints. Kiernan’s “hero” is a drunk, the barmaid is more of a hero in her fashion, and none of the traditional high-fantasy tropes come out in the wash: the sea troll’s daughter isn’t a nemesis, the town elders don’t have a reward to give, and nobody’s doing a particularly great job at anything. It’s all mundane failure in a fantastical setting, and I appreciate that cleverness; it reminds me a bit of Kiernan’s take on urban fantasy as a genre in her Siobhan Quinn novels.

Overall, the Queers Destroy Fantasy! special issue is a decent read. I’d have like to see a little more tonal variation, but the topics and approaches to the fantastic were different enough to remain enticing—a solid installment in the series, though I’d hoped for a bit more out of it. The stories are good, but for the most part not spectacular; worth reading, though.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.